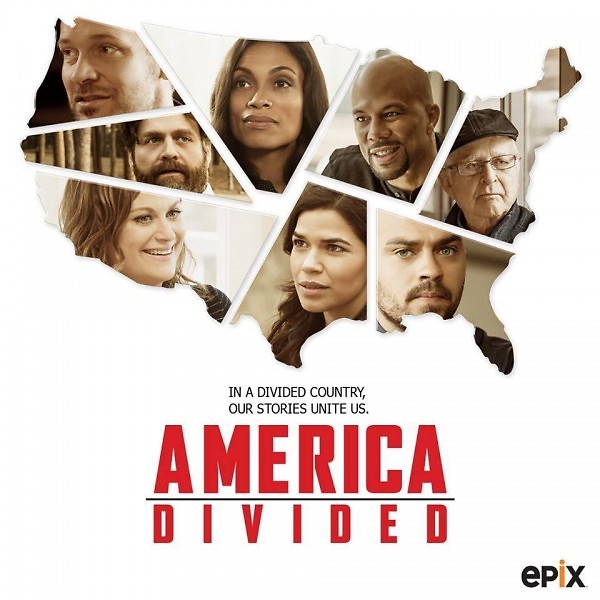

On Wednesday, June 28, over 600 people gathered at Celebration Cinema South to watch two screenings of America Divided, a film series that explores some of America’s thorniest issues—criminal justice, housing equity, education, immigration, voting rights, labor, Flint’s water crisis—by telling the stories of the people who get caught on those thorns.

The guide in each episode is a celebrity with a personal connection to either the issue or the place. America Ferrera is the child of parents who immigrated from Honduras; she explores the lives of undocumented workers in Texas. Common is from Chicago; he delves into criminal justice stories there. Jesse Williams was a teacher before he became an actor; he takes us to a failing school system in Florida.

Many of the people in the audience worked in social services, health, education and social justice, but there were also regular citizens. Devetta Clayton recently attended a racial reconciliation training at Church of the Servant, and she said, “I’m really trying to stay connected to what’s going on. Going through the adoption of my granddaughter, I saw a lot of privilege, of racism. I’m connected on a personal and professional level when it comes to the system.”

Connection is one of the broad purposes of this docu-series, both in terms of the connections among the eight parts, and connection between the people in the stories and the people viewing them. Producer Lucian Read, who was at the screenings, said, “One of the premises of this series is that you have to understand them together.” A.J. Jones II, Chief of Staff at the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, one of the major supporters of the films, highlighted this, as well. He said, “Any time you focus on one injustice issue, you know there are others. You can link them so people see a common thread of humanity in the process.”

In her segment, America Ferrera gets at the hoped-for connection between people: “It will only take a small amount of imagination to put ourselves in their shoes and see that they’re people.”

One of the reasons Denise Evans, Program Coordinator of Strong Beginnings, wanted to bring this screening to the movie theatre was because the audience is compelled to put themselves in the shoes of the people onscreen: they can’t look or walk away like they can if they’re watching a tablet or laptop screen. The audience is forced to confront the personal toll of these enormous and overwhelming issues.

It worked. With each of the four episodes shown on Wednesday, the mood of the audience got heavier and heavier. People gasped during the episode that explored housing issues in New York City, at an old clip of Archie Bunker where Archie says, “One colored family is a novelty. Two is a ghetto.” They gasped again when producer Norman Lear is part of a housing investigation that clearly showed the African-American applicant turned away because there were no apartments, and then the white applicant made an appointment to see a number of available apartments.

In the episode about five failing schools on the south side of St. Petersburg, Florida, each statistic brought muttering from the audience. Ninety percent of black students were failing math and reading. Classrooms had one teacher for 60 kids, and some had five teachers in one year. Primarily African-American students, some as young as six years old, were being arrested, handcuffed, interrogated without their parents present, and taken away in police cars for incidents such as kicking over a trash can and writing on a bathroom wall. Mary Brown, an activist in Pinellas County said, “I see a whole decade of kids losing.”

The next episode began with the video of Chicago police shooting 17-year-old Laquan McDonald 16 times in 15 seconds, and went on to the Cook County Jail where we learned that there are more African-American men in jail today than were enslaved at the beginning of the Civil War. The issues got personal and plaintive with a young boy who talked about his emotions when he found out his father was in prison.

Zach Galifianakis gave his episode a lighter feel, but the issues were just as deep: money, race, politics, and voter suppression. He said, “This isn’t a Republican or Democrat thing, but a North Carolina thing. A Southern thing. It feels like North Carolina has lost its way.” Rev. William J. Barber was blunt: “People are winning now not because they’ve won, but because they’re cheating.”

Producer Lucian Read is familiar with this reaction to the docu-series, as he attends screenings all over the country. “But,” he said, “we tried to show outcomes at the end with people doing things and both major and minor victories. We want to leave people with, not despair, but inspiration.”

Indeed, the screening ended with positive steps forward for each of the communities. In New York, the Fair Housing Justice Center (FHJC) sued the landlord with the racist renting practices—and the film notes that the FHJC has never lost a case. In Pinellas County, the newspaper, a federal probe, and an organization of local churches (Faith and Action for Strength Together) got the school board to make serious reforms and replace the principals of all five schools. In Chicago, as Common says, “A girl from the projects defeats a tough-on-crime prosecutor. A movement led by young women of color brings down the police commissioner…and a young father rewrites the future that seemed like it had already been written.” In North Carolina, the federal courts struck down their voter suppression laws.

The film also highlighted the words of Rosanell Eaton, now 95, who registered hundreds of African-American voters in the 1960s and was a key witness in the federal voting rights trial. When asked why she continues to work so hard, she says, “I just keep on going and doing. You only have so many days here, but this is for future generations. For ‘we the people.’ It’s not just for you.”

After the film, the audience heard from five local people who are all working hard to address the issues discussed in the docu-series. As Alison Colberg, Executive Director of The Micah Center said, “Everything we see in the movie is happening here in Kent County.”

They were there to suggest things audience members could do in response to what they’d just seen. As Denise Evans said, “Get angry. But get angry enough to do something.”

Colberg spoke about immigration: “There’s an entire generation of children living in fear and growing up in this era of mass deportation and mass incarceration of brown people. The Kent County Sheriff’s Department could decide not to cooperate with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)” by not holding people until ICE can get there to start deportation proceedings.

Mariano Avila, a reporter for WGVU, encouraged the audience: “Understand who you are...Try to figure out who your story intersects with others.' Try to consume stories that are coming from communities that don’t look like you.” Stacy Stout, co-founder of Latina Network of West Michigan and Assistant to the City Manager of Grand Rapids, issued a challenge: “Ask questions. There are a lot of racist people doing nice things. Push the status quo. Why do we do that? Who is giving us affordable housing? Who is getting the jobs you’re bringing?”

Dr. Andre Fields, counselor at Grand Rapids Community College, spoke about shared responsibility for the situation Grand Rapids finds itself in as the second worst city in the nation for African Americans. He said, “White people have downloaded a superiority complex. Until they unlearn that superiority, they’ll have a hard time having racial empathy. On the black side, we have to unlearn that internal sense that I can’t overcome racism and build the life that I want. We have to take responsibility for our homes, our churches, our neighborhoods.”

Ana Devereaux, an attorney with the Michigan Immigrant Rights Center, asked us to ask our city and state representatives about opening up driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants as one way to stem the tide of arrests for small matters that wind up in deportation proceedings. But she also highlighted something from the docu-series. She said, “The effort to create segregation means that we’ll have to have effort to break it up. And that’s true in every area. There has been much effort to create these systems that are unjust and we have to work hard to dismantle these systems. Sometimes I get discouraged…it’s hard, because we know there’s a lot of work ahead. But it isn’t undefeatable.”

To encourage Grand Rapids residents in that work and to keep this conversation going, the Grand Rapids Public Schools’ Parent University will host screenings of all five parts of America Divided between September 2017 and May 2018. Check the Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/americadividedkentcounty/ for more information.

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.