Dixie Olin’s house is littered with art. From the large mural of a beach scene in the dining room to the art projects on the deck to the ornate vases in the china cabinet, any onlooker can tell that the house is inhabited by an artist. As a local artist, she has a lot to say about the important role of art in the community, both for the individual and for society as a whole.

To begin with, Dixie thinks that art- or at least the desire to create art- is innate, “I think it is something you’re born with” she speculates. “Not any one thing makes you interested in art.” Dixie believes that “as an artist, it is your responsibility as a storyteller to expose the people around you to everything that is so busy and special.”

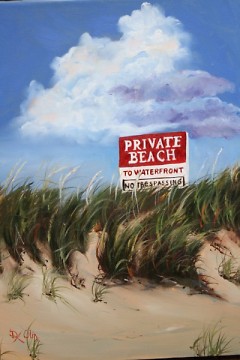

Never one to conform, Dixie has exposed her viewers to subjects as varied as motorcycles (she enjoys painting chrome, leather, and the weathered faces of motorcyclists) to the dune landscapes that she has entered in ArtPrize 2011, stirred by a need to make people aware of the preciousness of Michigan's lakeshore. Of those who might judge, she notes: “I got sick of trying to paint something and hoping someone would like it."

“You are a painter if you can paint five white eggs on a white plate in the sun and seven black dogs in the sun. With the sun, there is so much light and dark to play with. A painter must gently change the values of colors to distinguish the light from the dark and make five white eggs appear on a white plate and seven black dogs stand out from each other.” The light and dark contrasts on black leather are just as challenging for her in her motorcycle paintings such as “Hanging With Friends" as the more subtley toned colors and textures in her landscapes.

Dixie finds that no matter what the subject matter, she will paint for a while and then let it sit and dry, but she is still painting it in her mind. She’ll paint and erase and repaint in her mind several times before she paints again. “But I hit a wall and burned out last April,” she recalls. “Trying to make business decisions is difficult for artists.”

After months of focusing on chrome and leather, oftentimes attending motorcycle meetings to paint live, on-site, she needed a change. That's when the July deadline to enter ArtPrize pushed her to look for a new subject. Her hope with Saugatuck Dunes, as she states on her ArtPrize website, “is to draw attention to the choices being made regarding the dunes to the north of Oval Beach and the area's future.”

Dixie believes that art comes from some higher power. “It’s a gift that comes through me. That part that allows you to channel is the gift. Anyone can achieve painting, but your desire is your talent. It’s the same plug as writing or music. It comes from beyond here. An artist can take you places. A good painting should let you walk into it or have something come out at you. It’s an illusion. It’s magic.”

Dixie's views on ArtPrize and her advice regarding appreciating art are a conglomeration of individual desire, community response, and the history of art's relationship to religion and other institutions. “Somewhere in history, the freedom to appreciate art was stolen from a lot of people. I think it was a marketing and control issue.” Since the church financed a lot of artists, a trend that escalated in the renaissance era, they had the principal say in which art was “good enough” and which art wasn’t. “And since the church cut off so many artists, they have been starving ever since,” Dixie laughs.

Dixie believes that the freedom to appreciate art is still in danger. “Art programs are first to be cut in schools. And as a result no one can think outside the box anymore. In art there is something called abstract reasoning which is the ability to see something that isn’t there. Everything you use and see started as a drawing that helped to interpret the concept.” Objects we use every day like computers, books, money, and buildings all began as drawings. Someone had an idea and drew a picture.

Because Dixie sees art's usefulness all around her, she absolutely abhors the fact that art is the first thing to be cut in schools. “When you take art out of schools you are dumbing down children. It’s a national shame." ArtPrize isn’t a perfect animal, she notes, but art isn’t perfect. "But this opens doors to let people see some pretty wonderful stuff. More people come downtown during ArtPrize than anything else: young people, old people, middle aged people. And they are out talking to people, walking around outdoors, and getting along. And if that doesn’t show you the power of art, well, you’re dumb.” She laughs. “No, I mean if that doesn’t show you the power of art, then obviously you haven’t been down to ArtPrize."

It's not surprising then, that Dixie is uncomfortable calling any piece of artwork a 'bad' piece of art. “I think there are those that are artistically delayed, but it’s still art. I think there is art out there that is poorly executed, but sometimes delivers a message better.”

She describes this idea through children’s art. Children’s art, though often considered “bad” by onlookers, often conveys strong meaning. “I personally love children’s art. Part of losing confidence in art is when you were a child and someone gave you art supplies and you drew a line separating the page and you had earth and sky. Then you draw a square and a triangle and that’s a house. And then a line with a circle and that’s a tree. It’s easy. Somewhere around nine or ten someone says to you that’s not a tree, it’s a line with a circle. And you are crushed and say you can’t draw. This age is an age when you want things to be perfect. It’s the beginning of recognition and you have to find your way from there.” Artists, she explains, see their stick and circle and don’t listen to those who say it doesn’t look like a tree.

According to Dixie, “John Wayne Gacey, Ted Bundy, Adolf Hitler, Angelo Buno (the Hillside Strangler), Charles Manson, Henry Lee Lucas were all thrown out of art school. They were all rejected artists.” Dixie doesn’t necessarily see artistic rejection as a direct cause and effect for their violent lives, but she strongly believes that “the need to express yourself is a very strong force in anyone’s life, the need to be seen for yourself. If everyone had a way to express themselves, to release demons, to relieve and explain not only joy but also trauma, we would all be happier and less likely to feel alone in the universe. It's powerful stuff! Use it for good!”

Dixie’s three beach paintings entitled “Saugatuck Dunes, Lost Horizons”, are located at 80 Ottawa in Family Capital Management. You can see many of her motorcycle paintings on her website at http://www.artforbikers.com.

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.