The parents wanted to take him out of the United Kingdom for treatment. The hospital took the parents to court to prevent them from doing so. Ultimately, he died at the end of July after additional court battles regarding the parents’ desire to take their son home to die. Ultimately, he died in a hospice facility.

Should doctors, hospitals, and the courts have the right to tell parents what medical treatments they may and may not pursue?

Father Kevin Niehoff, O.P., a Dominican priest who serves as Adjutant Judicial Vicar, Diocese of Grand Rapids, responds:

“This issue is difficult because the heart strings conflict with the head strings. Being terminal means there was no hope of healing for this dear child.

“Archbishop Vicenzo Paglia, president of the Pontifical Academy for Life, states, ‘the interests of the patient must be paramount.’ (http://en.radiovaticana.va/news/2017/06/29/vaticans_academy_for_life_issues_statement_on_charlie_gard/1322138) Archbishop Paglia continues, ‘we must also accept the limits of medicine and avoid aggressive medical procedures that are disproportionate to any expected results or excessively burdensome to the patient or the family.’ (ibid.).

“The Catholic Bishops’ Conference of English and Wales issued a statement. Their words were pastoral, and ‘recognize the complexity of the situation, the heartrending pain of the parents, and the efforts of so many to determine what is best for Charlie.’ (ibid.).

“As a Catholic, when this issue arises, one must never act in a deliberate way to shorten or end life by removing nutrition and hydration to intentionally promote death. Instead, the soul of the individual is to be considered so that decisions may be humane by not only respecting the limitations of what must be done but also assist the sick person on his or her journey to natural death (cf. ibid.).”

Fred Wooden, the senior pastor of Fountain Street Church, responds:

“They are not preventing treatment, but rejecting payment. The British NHS refused to pay for something that had little chance of help but an assured immense cost. If Charlie got it, should not all those who need it also? The same dilemma is at the heart of all health insurance decisions, only less dramatically. Are we entitled to all treatments no matter how expensive and unproven? Like it or not, health care is rationed. We cannot all have it all. Right now money is the measure, and those who have more get more. But ethically speaking, as lives are supposedly of equal worth in society, we need rules that apply to everyone equitably. Were there to be such rules in place, even terrible outcomes could be accepted as fair.”

My response:

It is true that the National Health System of the UK refused to pay for experimental treatment for the reason that Fred Wooden outlined, but in this case the parents had raised enough private money to take their child out of the hospital to a doctor at New York’s Columbia University Medical Center for the experimental therapy that might extend their child’s life. The hospital’s decided to block the parents from taking the child on the grounds that this treatment was not in the child’s best interests. The European Courts agreed with the hospital’s argument that further treatment was futile and would cause the child pain and suffering in exchange for possibly extending his life a short time.

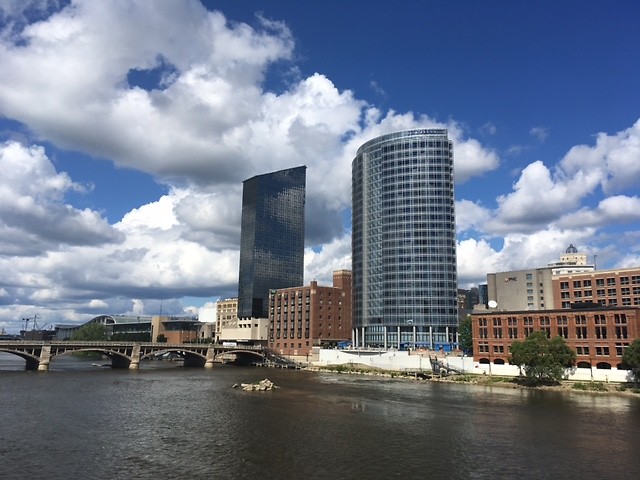

Had this happened in a hospital in Grand Rapids, the hospital may very well have agreed that further treatments were futile and refused further treatment. It is unlike that the hospital would have chosen to petitioned the courts for guardianship and taken the decision away from the parents. More likely, the hospital would have agreed to allow the child to be transferred to the care of a different hospital as long as the local doctors were convinced that the second hospital would take full responsibility for any consequences of the experimental treatment.

Making care decisions for an adult who can no longer express him or herself is difficult. Making such decisions for a child is ten times more difficult, and making decision for an infant is 100 times more difficult. Normally, we make ethical medical decisions based on the patient’s life goals and goals of care, especially regarding extending life versus additional pain. An infant cannot articulate any of this. In such a case, the hospital or the courts should rely on the parents’ sense of when to push for more treatment and when to let the dying process take its course.

In the case, however, I also believe that the parents’ desire to extend life for its own sake was not the wisest decision. The experimental treatment extended the lives of mice only 4 percent of their lifespan. Assuming the same results on a human being means that Charlie might live three more years. For a child with Charlie’s condition and limited potential because of brain damage, it hardly seems worth putting him through such pain and suffering. Better, in my opinion, to let nature take its course and return Charlie’s young life to God.

This column answers questions of Ethics and Religion by submitting them to a multi-faith panel of spiritual leaders in the Grand Rapids area. We’d love to hear about the ordinary ethical questions that come up on the course of your day as well as any questions of religion that you’ve wondered about. Tell us how you resolved an ethical dilemma and see how members of the Ethics and Religion Talk panel would have handled the same situation. Please send your questions to [email protected].

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.