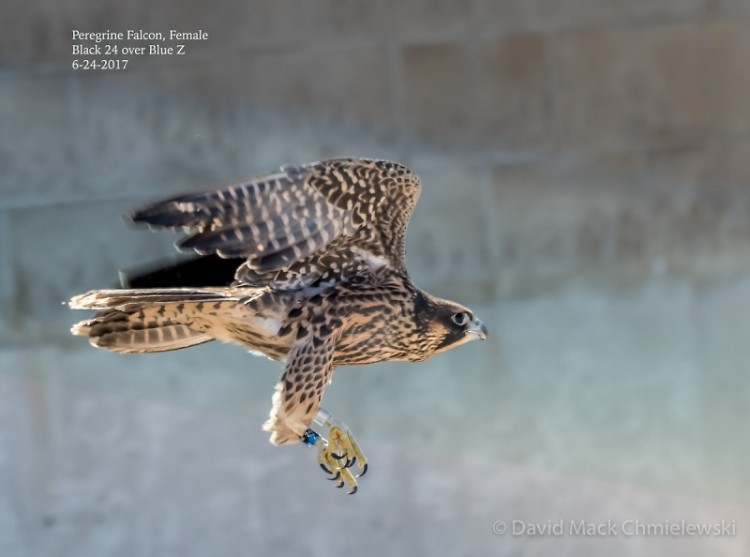

Peregrine falcons in Michigan are making a big comeback.

Thanks to decades of careful wildlife management – including installing man-made nesting boxes atop skyscrapers in Detroit, Grand Rapids and other southern Michigan cities – the world’s fastest predator is on the rebound and returning to its natural habitat in the Upper Peninsula.

Once extirpated in Michigan, biologists in the 1990s attempted to reintroduce them to their historical nesting locations in the cliffs of the Upper Peninsula.

“The U.P. was the place we thought they would all gravitate to immediately, but it wasn’t,” said Karen Cleveland, a Michigan Department of Natural Resources wildlife biologist. “But now those sites are starting to be used again in decent numbers by peregrines.”

Their comeback is delighting bird-watchers across the state.

Peregrine falcons are the fastest animal on earth. As the crow-sized bird stalks its prey, it soars to a great height and then dives steeply at speeds of more than 200 mph. Its diet includes birds such as pigeons, songbirds and waterfowl.

“You’ve got to respect any bird that can dive-bomb a pigeon in an urban area at 200 miles per hour,” said Gail Walter, a veterinarian and Audubon Society of Kalamazoo volunteer.

Listed federally endangered species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1970, the peregrine falcon was removed from that list in 1999 following extensive restoration efforts. Although its numbers are on the rise in the Great Lakes State, it remains one of only nine bird species classified as endangered in Michigan.

“The incredible recovery of peregrine falcons in Michigan and across the world is considered a textbook example of the effectiveness of wildlife conservation,” said Matt Pedigo, chair of the Michigan Wildlife Council, which was created to raise the public’s understanding of the importance of wildlife management.

Scientists attribute this remarkable turnaround to three things: Restricting the use of the pesticide DDT, legal protection banning the persecution of raptors, and helping peregrines colonize tall buildings found in larger cities in southern Michigan and across the Midwest.

Saved by science

Peregrines don’t build stick nests but instead scrape out depressions on high cliffs. Because of this distinct nesting site requirement and their position at the top of the food chain, peregrine falcons have never achieved abundance anywhere in the world.

Historically, fewer than 15 known nesting sites were in Michigan, all across cliffs in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

During the 1950s, the world population of peregrines was on the decline mostly due to the use of DDT in pesticides. DDT accumulations in the bodies of top predators such as peregrines, eagles and osprey cause them to lay thin-shelled eggs that break during incubation, making reproduction difficult.

“Eagles, osprey and falcon populations were pretty hard hit because the animals they eat had also consumed DDT and there was a cumulative effect as you went up the food chain,” Walter said.

By the mid-1960s, no peregrines were left east of the Mississippi River.

Michigan in 1969 was the first state to ban DDT after Michigan State University researchers provided data that strongly implicated DDT in the disappearance of songbirds on campus, Cleveland said. The chemical was banned in the United States and Europe in the 1970s partially due to data showing its effect on the decline of the peregrine falcon.

When restoration efforts began, the population of peregrines in the United States was down to 10 percent of its original size.

Urban living remarkably successful

The species’ restoration is due to successfully breeding birds in captivity and releasing them into the wild.

After mediocre results releasing chicks in the Upper Peninsula, biologists came up with a new plan.

“They said, ‘Skyscrapers look a lot like cliffs. Let’s see what’ll happen if we release them in urban areas,” Walter said. And it worked. “The birds have made cities their home,” she said.

At first, peregrines nested only in customized boxes created by the DNR and perched atop tall buildings. But they’ve since adapted and made their own nesting spots in other buildings and bridges.

Metro Detroit has the largest number of peregrines, but nesting pairs are also found along large waterways in cities including Grand Rapids, Kalamazoo, Muskegon, Ann Arbor, Lansing and Jackson.

Cleveland said the latest census showed approximately 35 nests in Michigan.

“Every year, we hear reports of new nesting sites,” she said. “Their numbers are slowly creeping up year after year.”

Returning to self-sufficiency

“Peregrine” means “wanderer” or “pilgrim,” which stems from the bird’s expansive territory and its typical migration to Central America each winter.

But because of an abundant supply of food in cities, most peregrines tend to stay year-round in Michigan.

Yet only about half of all peregrines survive their first year. The most common cause of death in urban areas is collision with buildings, bridges, and occasionally cars,” Walter said.

However, city living can help the birds, too.

When chicks nesting atop Fifth Third Bank are fledging in the spring, Walter alerts downtown Kalamazoo residents and businesses that the peregrines are getting ready to take flight.

“People really keep an eye out for the chicks, and if one of them should crash, they’ll let us know so we can rehabilitate them, if possible,” she said. “The whole city of Kalamazoo has really taken these birds under their wing, so to speak.”

Cleveland said the peregrine is territorial, so returning to its natural habitat in the Upper Peninsula may result from overcrowding in downstate urban areas.

“What’s amazing is that these birds have come back to the point that we no longer have to hold their hands so they will survive. Not every single nesting location is something created by man,” Cleveland said.

“Not only are they managing to find nest sites on their own, but they’re managing to successfully breed and survive in numbers high enough that they are expanding on their own,” Cleveland said.

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.