I recently sent the following letter to the Mayor and our City Commissioners as part of the End Circus Cruelty campaign, in which a significant and rapidly growing number of concerned Grand Rapidians are asking the city to pass an ordinance that would ban the use of wild animals in entertainment. I strongly favor the passage of such an ordinance, and here are some of the reasons that's the case.

Dear Mayor Heartwell and City Commissioners,

I am writing to express my full and enthusiastic support for the movement to end circus cruelty in Grand Rapids. We have an important opportunity here to join an increasing number of other enlightened cities that have had the vision to see that exploiting animals for the trivial purpose of entertainment is morally indefensible and should have no place in a civilized society.

I realize that it is tempting to read sentences like this last one as so much ranting from a sentimentally maladjusted "animal lover." To be perfectly truthful, that is probably how I would have interpreted the sentence myself a decade ago. Over the past 10 years, however, my scholarly interests as a professional philosopher working in the fields of environmental and animal ethics (sometimes collectively referred to in Christian circles as "creation care") have drastically changed my perspective on these matters. The truth, as I have come to see it, is that opposing animal circuses is the rational response to becoming educated about the kinds of beings that chimpanzees, elephants and tigers are, and about the methods that must be used to turn these intelligent, emotional, social and formerly free-living creatures into compliant, psychologically damaged, physically compromised and mostly-caged circus performers.

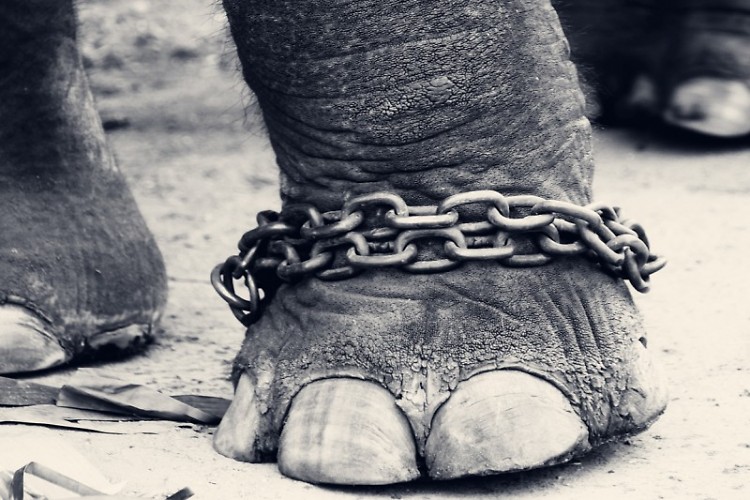

Common sense is the first harbinger of bad news for animal circuses. The picture will be bleak indeed for anyone who stops to reflect upon what traveling circus life must be like for big cats who have previously ranged over hundreds of miles with their prides, for elephants intelligent enough to collectively mourn their dead and for chimpanzees whose social relations and gestural systems of communication in the wild are dazzlingly complex. Even under "ideal" circus conditions, it is hard to imagine, upon careful consideration, that these creatures could be living anything but lives of perpetual frustration and abjection, where traveling in extreme confinement, training under whip and prod and performing unnatural actions under stressful circumstances are the norm.

Sadly, even minimal research into what life is actually like for circus animals shows that conditions are far from ideal and often horrific. Is it really that surprising that one would have to use cruel methods to compel smart, dignified creatures like elephants (who also happen to be enormous!) to perform degrading actions like prancing around in costumes and contorting their bodies into poses that are physically painful for them to achieve? Consider for a moment about how difficult it is to get our own dogs and cats to comply with the simplest commands when they have cross purposes, and now try to imagine getting an elephant to perform stunts without using intimidation and violence to "break their spirits" first.

For those to whom the prospect of "humane" elephant training seems plausible, I challenge you to test the adequacy of your intuitions against this video (warning: the video contains very disturbing images and offensive language). If you are concerned (as I am inclined to be) that one video is too small a sample to make an informed judgment, there are hundreds more to watch, just a Google search away.

When we combine our common sense about what animals are like with basic research into what animal circuses are like, it is difficult for intelligent people of moral character to escape engagement with very serious scientific and ethical questions- questions that may become all the more urgent for those who see the concerns of science and ethics as intimately connected within a religious frame of reference.

The scientific question is this: Is it possible for animals like elephants, tigers and chimpanzees physically and psychologically to thrive as performers in a traveling animal circus? While there may be veterinarians on the payroll who answer in the affirmative, the overwhelming majority of scholarly scientific literature in cognitive ethology strongly suggests otherwise- as a review of the references in any book by Jane Goodall, Jonathan Balcombe, or Marc Bekoff, among many other animal scientists, demonstrates.

The ethical question is this: Is it morally advisable to support an industry that systematically compromises the most basic interests of intelligent, emotional and social creatures merely for the sake of entertaining people? Let us acknowledge that no urgent human need is served by animal circuses, and even no desire to be entertained is served that cannot be adequately met by dozens of other comparable, similarly-priced or cheaper entertainment options that do not require the exploitation of elephants, tigers, chimpanzees and other animals conscripted into circus life. To answer this question in the affirmative is akin to saying that one's trivial desire to be entertained by exploited animals outweighs the most fundamental interests of those animals themselves. Unsurprisingly, the strong consensus among professional animal ethicists working in philosophy, human/animal studies and philosophical theology is that the answer to this question is a resounding no.

In light of these scientific and ethical questions, those who operate within a religious frame of reference might ask themselves this additional question: Is supporting animal circuses a defensible case of "good stewardship" for people who believe themselves to be appointed by a loving creator God to have benevolent dominion over these intelligent, emotional and social creatures whom God has called "good" and in whose flourishing God delights? Individual people of faith must answer this question for themselves, but those who wish to answer in the affirmative will find little support from leading religious animal ethicists such as Carol J. Adams (Presbyterian), Andy Alexis-Baker (Anabaptist), Dr. Charles Camosy (Catholic), Dr. Gracia Fay Ellwood (Quaker), Dr. Stanley Hauerwas (Methodist), the Reverend Dr. Andrew Linzey (Anglican), Dr. Jay McDaniel (Methodist) and Dr. Stephen H. Webb (Catholic), among many others.

I recognize that politics and governance are exceedingly complicated. There are always important practical trade-offs to make and competing interests to consider. Public servants are not in a position, I realize, simply to wave their wands and mandate everything that is arguably in the interest of the public good. Having said those things, it seems to me that public servants do have a tremendous opportunity that most citizens never have to stoke the fires of public moral imagination and to challenge their communities to lead by example when our best scientific and moral evidence demands more enlightened attitudes and actions in the face of outmoded conventions and institutions.

The best evidence suggests that animal circuses are inhumane and morally indefensible. The world at large is waking up to these truths, as is evidenced by the increasing number of cities and countries that are banning these enterprises. One day, hopefully in the not-too-distant future, I believe that animal circuses will be viewed by all people of conscience as lamentable moral travesties, perhaps almost as difficult for our great-grandchildren to understand as the travesties that people of color were once bought and sold as property and that women were once denied legal and political standing.

At the moment, this kind of language may sound grandiose or even perverse to people who have only a casual understanding of what "circus animals" are like and of what is done to them and of how they are made to live. But I challenge you to do the research for yourself, to go where it leads you and to shape your legacy of governance accordingly. I would be surprised if you came away with the sense that the concerns of your constituency about cruelty to animals used in circuses are unwarranted.

Thank you for your consideration.

Very sincerely yours,

Matthew C. Halteman*

Associate Professor of Philosophy, Calvin College

Fellow, Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics (U.K.)

Faith Advisory Council, Humane Society of the United States (Washington, D.C.)

*The views expressed in this letter are the author's and do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions with which he is affiliated.

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.

Comments

Test