Public art shapes the character of a place. The Calder stabile provoked a commotion of opinion when it was installed in 1969. Was it art? Was it a waste of money? Letters to the editor, pro and con, poured into The Grand Rapids Press for months. The sculpture was “welded junk”; it was “ageless majesty.” One prominent businessman, county supervisor Robert Blandford, paid for derisive radio ads in the weeks before the dedication. On the other hand it inspired the symphony to salute it with a modernist fanfare of Ives and Copland. And gradually it grew familiar; it educated our eyes. It’s become, at last, an emblem of the city, a point of pride among us and a mark of distinction to outsiders.

The Grand Rapids Art Museum has mounted an exhibit from its permanent collection (“A Decade at the Center: Recent Gifts and Acquisitions”) that invites us to reflect on what our civic art holdings are for. Should they mainly give pleasure and reflect who we are? Or should they risk taking us where we might not want to go?

These possibilities, though mixable, are in principle at odds. Pleasure is easy, education is hard—which is not to say that one is legitimate and the other not. GRAM catered to the first when it exhibited Princess Diana’s wedding gown in 2010; the Detroit Institute of Art did likewise last year when it mounted a Star Wars exhibit. In contrast, GRAM’s recent Oswaldo Vigas retrospective aimed, arguably, the other direction.

Recognition and estrangement are both artistic values. We’re glad when a work “speaks to us,” we’re glad when it “transports” us somewhere else. But the character of the collection we acquire and care for as a city will be shaped by our choices among these dueling interests.

GRAM redrafts a Collection Plan every five years. The plan offers a vision of the museum based on its history and local context to guide its upcoming acquisitions. The current plan addresses the museum’s limitations frankly. For instance, “the ability to present a comprehensive historical timeline of art, while desirable, is out of our reach.” Instead of filling the gaps, the plan proposes magnifying the museum’s strengths.

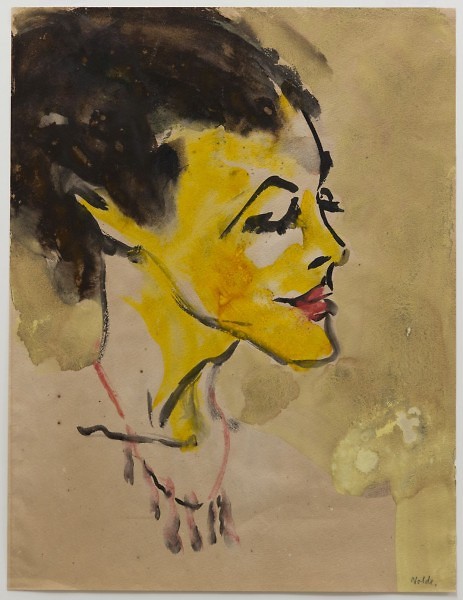

According to Director Dana Friis-Hansen, these strengths include European and Modern art, 1800-present; works on paper (prints, drawings, and photographs); and design and modern craft. The latter focus, rooted in West Michigan’s pioneering role in furniture design and manufacture, recently inspired the Kravis Design Center of Oklahoma to offer the museum a large collection of industrial design objects. One room in the current exhibition displays some of these, including a rotary telephone, radios, and a ski-bicycle hybrid. Some 200 such promised objects will have a significant impact on the museum’s future.

Decisions about what to collect aren’t made lightly. Every piece in the collection must be housed and conserved, so even donated objects involve ongoing commitment and expenditure. The museum does not, as a rule, sell or trade its possessions, which explains why it is extremely selective: it accepts only 1-5% of offered gifts.

From its founding in 1910 and into the 1990s, the collection grew almost entirely by gift. The 1966 Annual Report warned that, as a result, the collection “had grown in many directions without control.” Since the establishment of the museum’s first endowment in 1997, GRAM is in a better position to shape itself deliberately.

Given the priority of building on existing strengths, every acquisition has ramifications for the museum’s future. Ownership of the Richard Diebenkorn oil “Ingleside,” for instance, gave particular value to the offer of a print by the same artist. The same goes for the Kravis design collection: it’s welcome because it amplifies an existing strength. Both of these make sense, but they point in divergent directions. Fine art, or design? In principle we want it all, but limited space and limited resources force choices.

For me, “Ingleside” is an eye-opener. I want to visit it, and I’d be proud to boast about a notable collection by the artist. The other direction—increased devotion to manufactured objects, which might do as well at the Public Museum—is a letdown. I’d be sorry to see much more space and attention funneled that way.

Whether my sentiments are representative, it’s a public issue worth discussing, just as the Calder was 40 years ago.

The Collection Plan is due this year for its 5-year revision. The “Decade” exhibit makes clear that, in the spirit of the times, a likely priority will be to address the underrepresentation of women and minority artists. (New York City’s Museum of Modern Art has just undergone a major renovation along these lines). Here again is a chance to ask about the purpose of our museum. Should it reflect the population of the city, of the state, of the country? To what extent should it, must it, speak to social issues? To what extent should it, can it, aspire to being a house of beauty and visual discovery?

These are topics for another article. Meanwhile, as social issues go, the demand for diversity has this to commend it: it’s a familiar concern that is met above all by showcasing the unfamiliar. Thus it may just answer the question “Should the museum meet us where we are or take us somewhere new?” with “Yes.”

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.