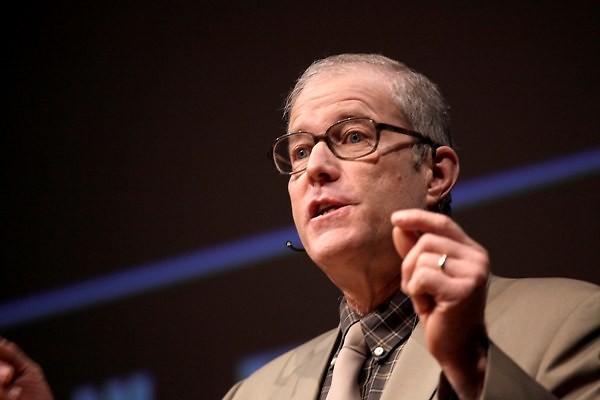

In a January Series lecture titled “Dancing With Dinner,” alternative farmer Joel Salatin promoted a radical change in the way we think about food and its production.

Salatin, a self-proclaimed “Christian libertarian environmental capitalist,” lives and works on his own Polyface Farm in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. He has authored nine books, most recently Folks, This Ain't Normal: A Farmer's Advice for Happier Hens, Healthier People, and a Better World. The book title reflects Salatin’s speaking style, which is marked by its good-old-boy quirk and vibrancy.

Salatin’s speech opened with a lament for the long-passed days of a food experience that was fundamentally local. In 1946, more than 50% of food came from within 20 miles of its point of consumption. On average, food travelled 40 miles from its source, he said. That was only six decades ago.

“Now, people call soil ‘dirt’,” Salatin remarked. Food is regularly consumed states away from the site of its production. Salatin calls this a mechanical approach to food. His ecological outlook, on the other hand, he sees as biological. As the title of his speech indicates, he adopts an intimate view of food sourcing. On his farm, this perspective translates to farming methods that are anything but conventional. Salatin explained how Polyface Farm aerates its manure: pigs nose through corn-ingested manure, which converts the compost from anaerobic to aerobic. The process, he said, capitalizes on the animal’s distinctive “pigness.” Practices like this are what set Polyface apart from its farming peers.

Salatin’s ingenuity is what makes all of that possible. Salatin’s speech, much like this farming habits, was inventive, animated in its delivery and passionate in its pleas. He likened his cows, herbivores and the lifeblood of most farms, to a “biomass restart button.” On the virility of pollen, especially his neighbor’s unwanted, artificially-enhanced pollen, Salatin quipped, “You think people are promiscuous, you oughta see pollen on a jet stream.”

The lecture built to a call and a challenge to restore the lost intimacy between humans and their food. In an earlier session exclusively with students, Salatin criticized modern attempts to “extricate ourselves from our ecological umbilical [cord]” and the contemporary fragmentation of society—the stark segregation of commercial and residential properties and the division between food-producers and food-consumers. He encouraged consumers to dirty their hands in a garden and farmers to “take a bath, get a suit and read.” Food is the tie that binds us all, he argued: shouldn’t food be our “pharmacopeia?”

This mindset is what inspires Salatin to, as he says, “bring a moral dimension to the more mundane, visceral aspects of human life.” He calls his work land redemption and sees serious consequence to the way humans handle surrounding biological cultures. He counters criticisms of elitism or impracticality with the idea that his biological approach to food-sourcing best respects the wonder and intricacy of creation and its creator. He challenged attendees to appreciate that new creation as “a dance partner that we can embrace.”

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.