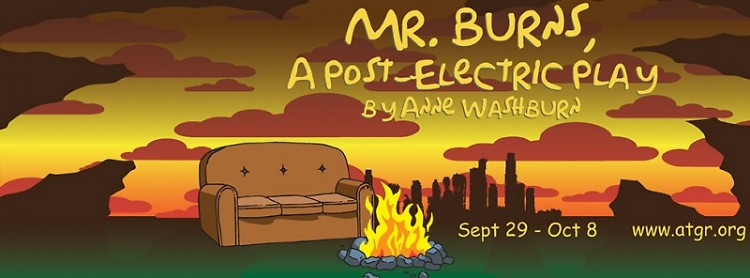

Actors’ Theatre of Grand Rapids opens its ambitious 36th season with a dark comedy that the New York Times called “so smart it makes your head spin” — Mr. Burns, a Post-Electric Play by Anne Washburn. The play premiered in 2012 at the Woolly Mammoth Theatre in Washington D.C., and appeared in New York at Playwrights Horizons in 2013.

The story defies simple summary, but a brief description: In the not-too-distant future, mankind has suffered a planetary apocalypse. Some survivors are gathered around a campfire—electricity is now a thing of the past—and as humans do, they’re telling stories. By way of comforting themselves, they begin to recall the plot of an episode of the TV show The Simpsons, urging each other on and filling in remembered details. The episode is “Cape Feare,” in which Bart, the son of Homer and Marge, is being menaced by the murderous Sideshow Bob.

Jump to Act II: It’s seven years later, and the group has coalesced into a proto theater company, and the storytelling has evolved into a fascinating mashup of pop cultural references, complete with live musical commercials, all bent by the prism of recollection. Act III is set 75 years after that, by which time the story has taken on the gravitas of Greek theater and has become the demented but deadly serious high culture of the New World.

“I first got my hands on the script because I started looking online and seeing what theatergoers were saying about it,” says director Randy Wyatt. “People either loved it or hated it, and they had equal crazy passion in both directions. So I’m like, OK, I’m listening. This is the kind of work I think is cool and could shake up Grand Rapids a little bit.”

Wyatt is program director for theater at Aquinas College, and is himself a multinationally-produced playwright. He’s been teaching the play in his theater history classes at Aquinas, because, he says, “it’s like the last leg of theater history. You’ve learned about postmodernism, you’ve learned how we got here, and now here’s this play that’s reaching back through all these styles, and in the third act you take all those styles, add what you know about pop and electronic and musical culture, and synthesize a projection of what a new theatrical style might look like 75 years down the road. That thought just blows my students’ minds, as it blew my mind when I read the play. It’s a script that is so worth exploring.”

You don’t need to be a Simpsons fan to follow the thread of Mr. Burns. Its characters are simply the framework upon which playwright Washburn chose to hang her metatheatrical tale. They are a starting point for identifying shared cultural references, which spin and spin into a form that, though it’s brand new, harks back to the origins of theater itself.

“If a Simpsons nerd comes to see this show,” Wyatt says, “they’re going to be like—that’s wrong, that’s wrong, and…yeah, that’s the point! There’s no way to go back and check now. We are post- electricity! So it’s not based on The Simpsons, it’s based on what we remember of The Simpsons. And as we go forward it becomes a Xerox of a Xerox of a Xerox. So when you get to Act III and it’s two generations later, you’re seeing all these mythic elements that have come into it, all these melodramatic elements, yet you still have faint echoes of what used to be The Simpsons. And the stories have become epic.”

Wyatt feels that our immersion in TV and movies has moved us farther and farther away from one of the original purposes of theater: catharsis.

“Act III is so much about communally purging emotions,” he says, “and our audience may think, oh that’s what that audience needs, because of the apocalypse. But where do we get to purge emotions from all the stuff we’re getting off electronic media? Where do we purge all our angst about Trump v. Clinton, how do we do that? Because just writing comments on the Internet is not how it actually works. The devaluing of theater as a civic function has had an effect on us, and is something we should be thinking about on a much bigger scale. I don’t mean to denigrate movies or even pop theater pieces, but do they do the same thing? I don’t think so. The Greeks had it, the Neoclassics, Shakespeare, but—what do we have? I think that’s a question the play addresses.”

“Mr. Burns really attracts me from that perspective. This isn’t a film we’re putting onstage, this is a piece of theater that morphs right in front of your eyes into different genres. All these things are happening right in front of you, the audience has no choice but to go along with the breathtaking pace, to keep up and put the pieces together instead of having everything spelled out for them, which I really appreciate about the script.”

Wyatt thinks that theatricality is a balm in our anxious times, and viewers of the play will be drawn in to the ancient urge to share our stories.

“Mr. Burns looks at how things morph over time, the reasons things are kept and why they are thrown away. People right now are into apocalyptic storylines—the apocalyptic narrative really rings true, for whatever reason. So Simpsons + apocalypse is the initial draw. But when you go deeper, you’ll see it’s not a play about The Simpsons at all, but about the enduring vitality of live storytelling. It brings us back to this very human idea that we are performative creatures, and we can’t help ourselves, we have to engage in this process. I love that.”

Mr. Burns, A Post-Electric Play runs September 29–October 8 at Actors’ Theatre of Grand Rapids at Spectrum Theater, 160 Fountain St. NE.

Further information is available at www.atgr.org.

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.