In a sense, having a distorted or inaccurate view of the truth is like playing the telephone game. The truth keeps getting interpreted and reinterpreted until the perception of reality is almost completely wrong. This distortion of truth is the myth that writer/director Chad Friedrichs set out to debunk through his enthralling and award-winning documentary, “The Pruitt-Igoe Myth.” Combining amazing archival footage with interviews of five former residents, Friedrichs succeeds in showing the rarely heard perspective of life inside Pruitt-Igoe.

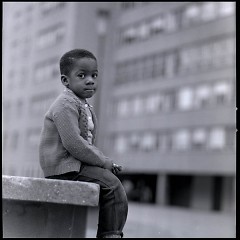

The film, which was screened at Urban Institute for Contemporary Arts (2 West Fulton) last week, begins with a shot of a car driving through a wooded road past skeletons of buildings and overgrown weeds, haunting music set behind a voice-over of a man headed back to his former home at Pruitt-Igoe. A highly anticipated government housing complex upon its conception in 1956, Pruitt-Igoe was supposed to relieve the overpopulation of an ever growing city of St. Louis and provide relief from the unsafe and unsanitary conditions of the slums.

However, the city wasn’t growing anymore. It ended up losing massive population around the time World War II was ending and black families began migrating north looking for factory jobs. By the time the 33 11-story apartment buildings were built, most of the factories were closing or had already closed. As the factories were closing, the city became further segregated as white families began to move out of the city, due to what the film describes as "a national pro-suburban policy." Pruitt-Igoe is now infamous for its collapse, which resulted in the nationally televised demolition of the buildings in 1972.

The most popular explanation for the death of Pruitt-Igoe, according to the narration, is that the people who lived there were simply too uneducated and too poor to thrive in a nice environment. People would often say they “caused their own problems, and had taken Pruitt-Igoe with them.” The film effectively shows that is a distorted view of the truth, and while the film doesn’t make the argument explicitly, the expertly-placed archival footage and interviews create the narrative that Pruitt-Igoe wasn’t always such a bad place to be.

“They were putting me on the 11th floor, with elevators” one former resident recalls fondly, “once I moved in…I called it the poor man’s penthouse.” While she may have called it the poor man’s penthouse, adult men were not allowed to live in Pruitt-Igoe, which meant families were being torn apart just so they could have what was supposed to be a better, more affordable home. The film narrative suggests there is no way to sustain such a large project while at the same time disrupting the family structure so greatly.

What makes this documentary particularly heartbreaking is the potential that Pruitt-Igoe had to really improve thousands of poor people’s lives. Instead, as the film suggests, pressures from conservative politicians forced the funding to be cut severely, causing maintenance to suffer. Once the maintenance stopped, lights were broken, allowing outsiders to lurk in the hallways and stairwells to rob residents as they walked by. The film argues that because of this lack of maintenance, the residents of Pruitt-Igoe developed disdain for any public figure. When the police were called, according to one interview, rocks and garbage would come raining down from broken windows. He said It got to the point where the police just stopped coming because of how they were received at Pruitt-Igoe.

“I know lot of bad things came out of Pruitt-Igoe, I know they did, but I don’t think they outweigh the good because at first, Pruitt-Igoe was a wonderful place. I believe Pruitt-Igoe would be here today if it was maintained like it was when they first opened it up,” said one former resident. While Pruitt-Igoe remains a stain of the city of Saint Louis, “The Pruitt-Igoe Myth” shows a first-hand look of the joy and comfort the complex created, and suggests that this could have continued had policy makers actually cared about its residents.

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.