We welcome back Kyle Kooyers, as we continue our series from the Kaufman Interfaith Institute staff. Kyle began working at the Kaufman Interfaith Institute while a graduate student at Calvin Theological Seminary, and then joined us full-time as Program Director upon completion of his Master of Divinity degree. Last summer he was appointed Associate Director.

Martin Luther is often credited with the saying, “Even if I knew that tomorrow the world would go to pieces, I would still plant my apple tree.”

Perhaps as the weather has begun to warm, you like many of my neighbors have made your way outside to garden, plant, or landscape as a means of catharsis during this Covid-19 season of social distancing. For a number of reasons, I too see planting as a beautiful practice during times of uncertainty, frustration, and fear.

There’s an aesthetic element in which we are working to beautify our space, finding a centering in something within our control. There is a grounding element as we connect with the richness and life found in the dirt of the earth. And there is a hope element as we invest in something that will blossom and yield in a future that may be difficult to imagine.

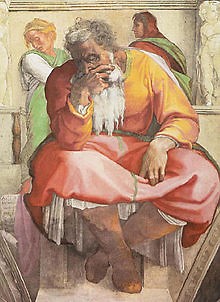

That notion of hopeful investment in spite of the present has always fascinated me. The prophetic texts of the Hebrew Scriptures are full of accounts where someone does something simply because it stands in contradiction to the situation or reality they are facing. One such example involving the Prophet Jeremiah comes to mind.

To set the stage, the city of Jerusalem is under siege by a massive army. The people of Israel are about to be captured and taken to Babylon. The world is literally falling apart around them. All of the things they loved to do, the plans they had looked forward to, their jobs and routines, the closeness of family and friends was suddenly taken away.

Amid all of this chaos and uncertainty, Jeremiah, who is effectively in prison for peaceful protest, receives a divine message that his cousin is about to offer him the opportunity to buy some land. Sure enough, his cousin Hanamel comes along and asks if he will purchase a field. So Jeremiah buys that field from his cousin, but he does so in the most official way possible. He pays 17 shekels of silver, signs two purchase deeds, and has the transaction witnessed and seen by all of the people who are sitting around him. The deeds are then given to his friend, Baruch, who places them in earthen vessels so they would be maintained for a very long time.

But this makes absolutely no sense! On the level of property value alone, it is a ludicrous investment. Jerusalem is under siege and the people of Israel are about to be carried off into exile. The land is about to be taken from them.

This purchase of land, this investment in the dirt is an embodied prophecy, a peaceful resistance to the idea that terror and destructive power will have the final word. It is a message that one day this very ground will see healing and prosperity. This action of hope ought not to be confused with a mere denial of the present situation, bleak as it may be. In this seemingly non-sense prophecy, Jeremiah literally invests in the hope of a future, a new reality, precisely at a time when that future seems utterly impossible, perhaps unimaginable.

For those living, or better, surviving, in the grip of captivity, disenfranchisement, oppression, or in the midst of a global pandemic, a message like this would seem like nonsense. But, at the heart of Jeremiah’s prophecy is both the acknowledgment of the present darkness and a bold move towards a future beyond it. This is not blind optimism. This is the action of hope in which Jeremiah acknowledges despair and still proclaims that peace, justice, and healing are possible.

I recently watched Jimmy Fallon’s interview with renowned researcher, professor, and author Dr. Brené Brown, on “The Tonight Show.” Dr. Brown discussed how to navigate the vulnerabilities associated with being in a situation for the first time – like a pandemic. She offers three helpful approaches:

• Naming that this is the first time we have encountered something like this.

• Taking the perspective that this will not last forever and will end at some point.

• Keeping our expectations in check since nothing is going to go as we planned.

For Dr. Brown, even with the despair and disillusionment of Covid-19, there is still potential for the future. She says, “I know for sure that we will have a huge opportunity to be better than before we went into it. I know for sure that a crisis like this shines a light on fault lines in our community, in our families, in our country, in our services, and we are seeing that. We are seeing disproportionately affected people.”

With an eye towards the unknown, Dr. Brown remarks, “We will have an opportunity as we come out of this to say, ‘You know what, we will not let this continue, this is not who we want to be as a country.’”

This is a true portrait of hope in the face of deep pain and immense loss. There are no easy answers. There are no platitudes or clichés to make it all go away. The suffering is real and the hurt is deep. Yet there is also an invitation – that we too might buy up fields in hopeless places and fill up our own little jars that something better is one day to come.

For some, like my neighbors, it looks like planting flowers or vegetables. For some it looks like sewing masks or donating to a local food pantry. For some it looks like confronting head-on the systematic disparities and inequities amplified by this virus. For some it looks like walking 2.23 miles in the hope of justice for Ahmaud Arbery. For some it looks like taking up a new hobby or returning to one for the first time in years. For some it looks like mustering just enough strength to sit up in bed and face the day.

Dr. Brown concludes, “I think for sure we will have an opportunity to be better and I hope we seize it. I know there will be more trauma coming out of this especially for those of you in the epicenter, there will be more trauma than we expect. And I know we are stronger than we think.” For all of us, hope means reentering and reimagining the routines and rituals we used to do, learning how to love and stay connected to people who are now at a distance. Moreover, hope looks like practicing neighborliness in new ways, offering patience, kindness, and understanding as together we invest in the unknown – a better future for all.

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.