We currently live in the Quaternary Period which is divided into two parts. The first being the Pleistocene epoch which lasted almost 2.6 million years. For the first 1.8 million years of it Michigan was occasionally covered in a mile-high sheet of ice. During this time there were four separate stages of glacier advancements of the Laurentide ice sheet interspersed with warm periods.

The period popularly known as “the Ice Age” was the final stage known as the Wisconsin. It was during this time the Great Lakes were formed as well as many other present day lakes in the north. This glacial movement also dropped the sea levels by hundreds of feet which formed the Beringia land bridge between modern-day Siberia and the state of Alaska. It is believed that around 13,000 years ago Homo Sapiens from parts of Northern Asia migrated to North America using this route.

Michigan was now two peninsulas surrounded by vast seas of fresh water. Large creatures roamed the state including a giant 250-pound beaver known as Castoroides, the Jefferson mammoth, and the American Mastodon.

Around 300 mastodon fossils have been discovered in the state, including Grand Rapids, the most intact being found in Owosso in 1940. It was named the state fossil in 2002 and is still on display at the University of Michigan’s Natural History Museum. Horses and camels were originally from North America. Both animals utilized the land bridge to spread into areas like Asia and Europe.

There was an excitation event at the end of the epoch which is believed to have been caused by climate change and humans over-hunting. The end of the Wisconsin glacial period ushered in the current Holocene Epoch, and the current warmer interstadial period we presently live in.

The four cultural traditions of the Eastern Woodlands begin with the big game hunters who are thought to have migrated from the south around 12,000 BC when the glaciers receded across the state. At the time Michigan was a dense forest of spruce and fir trees which provided a nice habitat for the nomadic Paleo-native tribes that numbered around 25 a group. They used fluted stone points at the tip of their spears to orchestrate coordinated hunts against large mammals who were abundant in the region.

This gave way to the Archaic period that saw the rise of the Old Copper Culture in the Great Lakes area. Two burial sites in Wisconsin show the intricacy in which the copper was worked by cold and hot hammer.

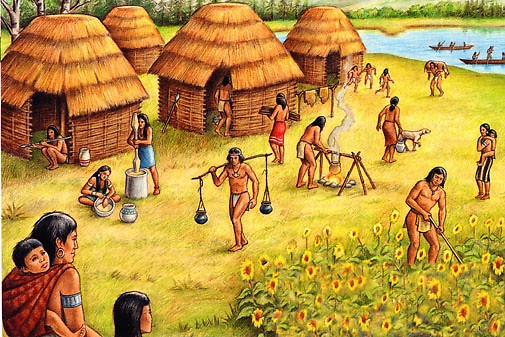

Around 3,000 years ago when David became King of Israel and the Iron Age was beginning in the Eastern Hemisphere the Woodland tradition was beginning in the west. In the Ohio River Valley a group of Native American societies that shared burial and ceremonial traditions began. They were the first of three mound building cultures to inhabit the Midwest. They had evolved agricultural practices and artistic works. They ceremoniously buried their dead in large mounds featuring items from their extensive trading network that stretched from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast. A few hundred of these mounds still exist in the present states of Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.

Corn was introduced to the Midwest during the mid-Woodland period. This crop along with the advancement of clay storage containers allowed for the advancement and growth of their culture which progressed into a wider culture that spread across the Great Lakes States known as the Hopewell.

The Hopewell were a confederation of different tribes that utilized a vast trading system. The tribe that inhabited the Western Michigan area including Grand Rapids are referred to as the Goodall. Their projectile points have been found in both the Kalamazoo and Grand River valleys. The Norton Mound Group located in the southwest outskirts near Millennium park are from this period. They are the best preserved mounds in the Great Lakes region and the only ones left out of the original 46 in the Grand Rapids area.

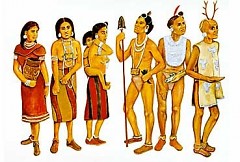

The Hopewell culture evolved over time in their artwork and craftsmanship. The later woodland cultures that followed the Goodall reflect some of these same behaviors as well. In the late 700s AD the aborigines of Canada who had been moving east from the Atlantic seaboard for a 1,000 years ended up at the Straights of Mackinaw. This culture of people were the descendants of the earlier woodland period cultures, and collectively called themselves the Anishnabeg. They had divided themselves into three groups. The Ojibway known as the elder brother, the Odawa, known as middle brother, and the Potawatomi, people of the place of fire.

During the 19th century two groups of mounds were located between Bridge Street and Fulton Street on the west side of the river. The artifacts in these mounds reveal a sophisticated culture that made ornate pottery and engineered, by hand, tools that they used to carry out their everyday lives. Sadly, the pottery, pipes, tools, and bones were sold or traded and the mounds began to be dismantled as early as 1850s, to make room for the expanding city.

Thomas Porter, who immigrated from London and eventually ended up in Grand Rapids in 1854, collected archaeological artifacts from around West Michigan. Many times he joined expeditions for the city’s museum providing sketchings and notes that are still available today at the downtown library.

One of the discoveries was in 1885 when they uncovered the contents of the Converse mounds, the largest of the groups. The find revealed a culture of residents that inhabited the Grand Rapids area around the 15th or 16th century. Radio carbon testing would not appear until the 1940s so they determined the age by the trees that were growing on top of the mounds. In their notes they mentioned the inaccuracy of this method and believe the artifacts could be older.

Other than what is learned through their artifacts, very little is known about the Native American populations that lived in the Grand River basin. It is not known what happened to last of the mound building cultures.

Michael Tuffelmire is a board member on the Grand Rapids Historical Commission. Visit their website for more information about Grand Rapids history, historygrandrapids.org

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.