Grand Rapids police drones often flown in Hispanic, Black, poor neighborhoods

Grand Rapids Police Dept. drones are disproportionately flown in Hispanic, Black and low-income neighborhoods, raising privacy and over-policing concerns. However, data shows drone usage has stayed within the parameters of the GRPD policy approved in 2023.

Grand Rapids Police Department drones are disproportionately flown in neighborhoods with high concentrations of Hispanic, Black and low-income residents, according to a review of nearly 250 drone flights from September 2023 to March 2024.

The data, which The Rapidian obtained through a public records request, is the first look at where and why city police have used the drones since the police department bought eight of them in August 2023.

In August, city leaders said the drone program would be subject to a high level of oversight with guardrails on what the technology can be used for. According to an analysis of the drone usage data, the drones have been used to assist regular police operations — not to monitor unassuming citizens.

Opponents of the GRPD drones had concerns last summer that the drones would infringe on residents’ privacy, but the new data has shifted some advocates’ initial fears.

“I'm less concerned about how they've been using the drones and more concerned about where they've been using the drones,” said Dayja Tillman, a legal fellow with the ACLU of Michigan, based in Grand Rapids, who opposed the drones when they were first approved in 2023.

The areas where they’ve been deployed replicate preexisting policing trends that harm marginalized communities, Tillman and policing experts say.

Just over half of the time, 51%, drones were flown in neighborhoods where there are over triple the average percentage of Hispanic or Latino residents. Similarly, 40% of the time GRPD drones were flown were in neighborhoods where there are over double the average percentage of Black residents. And a majority of the time GRPD drones were used, 61%, drones were flown in neighborhoods where over a quarter of its residents live in poverty.

Demographic and economic data used in the analysis are from the 2017 American Community Survey by the U.S. Census Bureau, which is the most recent information at the neighborhood level and the data that the City uses. In 2017, 13.8% of the city’s population was Black, 4.9% was Hispanic or Latino and 16% lived in poverty.

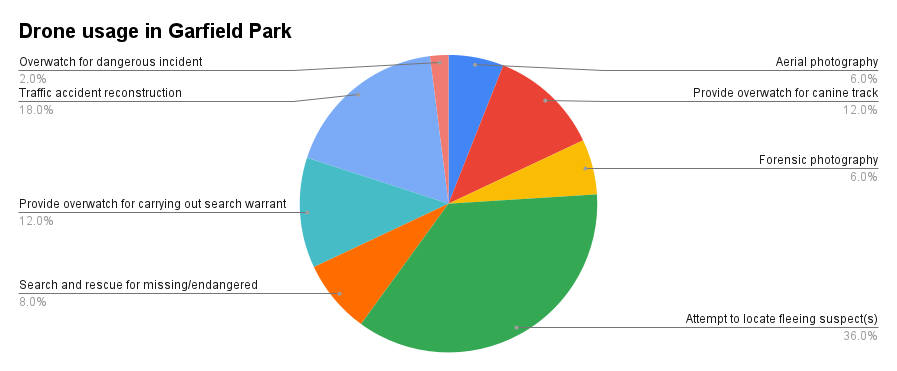

Forty drones were flown in Garfield Park within the six-month period for which data is available, the most of any neighborhood. Southeast Community had 36 drones flown, the second highest. The population of white residents in both neighborhoods is less than a quarter.

Aaron Kinzel, a criminology and criminal justice professor at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, said increased police presence in marginalized communities is nothing new.

“It’s the old trick,” he said. “It’s a practice that has gone on forever.”

Kinzel said areas with more police, especially when assisted by new technology like drones, can lead to higher incarceration rates.

GRPD’s drone usage is a reflection of “harmful policing practices” that can be seen across the country, Tillman said.

Matthew Guariglia, a senior policy analyst at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an international non-profit digital rights group based in San Francisco, Calif., said it's also a self-fulfilling prophecy. When there is an increased police presence in an area, police observe more crime, which results in higher crime rates and further scrutiny, he said.

“There's a presumption that these neighborhoods will be more dangerous and warrant more oversight or surveillance,” Guariglia said.

Police Chief Eric Winstrom disagreed that the drones’ disproportionate usage presented a problem, saying he’s “pleased that the data shows what it shows.”

“I am not surprised that drones are more often deployed in those locations because that's where the crime is occurring,” Winstrom said.

Winstrom said a host of socioeconomic factors can explain why crime is concentrated in marginalized communities, such as redlining and disparities in the education system.

Police seek to combat those forces by partnering with local advocacy groups and addressing and preventing violence. They also are ready to change their policies if policing practices prove harmful to marginalized communities, Winstrom said.

“Police are a very important part of this puzzle of lifting up people, of getting communities in a better place,” Winstrom said.

While concerns that police target Black neighborhoods are common, Michigan State University criminal justice professor David Carter says that officers are just following the data.

“Where we have more calls for service, we simply got to put more officers there,” Carter said.

And where police go, drones will follow. Carter said that more and more law enforcement agencies are using technology to assist their operations.

What drones are used for

After hearing public input about the proposed purchase of drones in 2023, city leaders landed on a policy outlining what drones can and can’t be used for.

Under the policy, drones can’t be used for “random or routine” surveillance, personal use or to “harass, intimidate or discriminate against any individual or group.” The drones can’t be equipped with weapons or facial recognition capabilities, and can’t use artificial intelligence. They can be flown up to 400 feet.

Jennifer Kalczuk, the GRPD public information officer, said drone usage by Grand Rapids police is “purpose-driven” and “drones are not operating without a very specific reason.”

The police department must submit detailed data on every drone flight to the Office of Oversight and Public Accountability (OPA), including the time the drone was in the air, the location it was deployed to and the purpose for its usage.

OPA evaluates data in response to formal complaints or in compliance with the Annual Report to determine whether it complies with city policies. It presents its findings in a surveillance report that covers GRPD’s drones and other surveillance technology owned by the city, including license plate readers and body-worn cameras.

City officials said no complaints regarding GRPD drone usage have been submitted.

OPA Director Brandon Davis told The Rapidian he didn’t want to make a predetermination on the data before officially reviewing it for the next surveillance report, which will be released in April 2025.

Data from the program's first six months show that police followed the city’s requirements for drone usage. The department used drones to oversee and assist police operations.

Drones were used to provide overwatch when police carried out a search warrant about 32% of the time.

When officers approach a house they have a warrant to enter, typically another officer is stationed across the street watching for fleeing suspects or any potential danger, said Captain David Siver, who oversees the drone program.

Drones have largely replaced that function, giving officers a better view of the premises. The drones give police and canines the ability to know what’s blocks ahead of them as they try to locate individuals, Siver said.

Nearly a quarter of the time, 24%, drones were used to track down fleeing suspects.

He said that the bird’s-eye view that drones provide is also helpful when reconstructing traffic accidents or in forensic photography.

According to the data, drones were used twice to assist the city’s Homeless Outreach Program. Siver said they were likely used to spot whether there were homeless encampments in heavily wooded areas.

The technology has the potential to ensure the safety of the community during police activities as well, Siver said.

For example, a drone could alert officers entering a house or chasing a suspect down the street of any bystanders out of their view that they should watch out for.

“It just gives people intelligence and information to make decisions and to keep … everybody involved safer,” Siver said.

Drones are allowed to oversee “civil unrest,” according to the policy. But so far, the city hasn’t had any large demonstrations that have needed oversight, Siver said.

While drones have yet to be used to monitor large gatherings, Guariglia says the fact that policy allows for it could have a chilling effect on activism.

“I think people would be less willing to practice those constitutional rights if they knew that at every protest they went to, there were gonna be drones flying overhead, monitoring everybody in the crowd,” Guariglia said.

Guariglia said GRPD’s policy guiding the use of drones is “a step forward.”

“In a lot of places, there are no restrictions on how police use technology of any sort,” he said.

Drones owned by other local law enforcement agencies don’t have to abide by the city’s restrictions when being used within its limits, Winstrom said.

“Just as I don't write use-of-force policies for the county or the state, I can't write their drone policy either,” Winstrom said.

The Kent County Sheriff's Office said the agency uses its drones in Grand Rapids if it is conducting a criminal investigation in the area or if another law enforcement agency requests it.

The Kent County Sheriff's Office “evaluates every request to ensure privacy concerns are protected,” Public Information Officer Kailey Gilbert wrote in a statement.

Community concerns

Some community leaders see the disproportionate deployment of drones in Grand Rapids as a reflection of larger, systemic structures that harm marginalized communities.

“It's all put in place by the powers that be, hovering way over top,” said Ned Andree, a Boston Square Neighborhood Association board member, at a recent neighborhood meeting in the southeast side of Grand Rapids.

But it should also be a wake-up call for residents to do more to prevent violence in their neighborhoods, said member Benton Shumpert.

Shumpert said change needs to come from the top down and the bottom up to truly address crime in neighborhoods.

“We can all do better,” Shumpert said. “Nobody gets all the blame.”

The City must create conditions where residents can truly thrive in order to reduce crime and the need for drones, like affordable housing and resources for small business owners, they agreed.

Andree also stressed the importance of strong relationships between police officers and the communities they serve.

Regenail Thomas, chief executive officer of Seeds of Promise, a nonprofit urban community improvement initiative in the Southeast Community of Grand Rapids, said he encourages his neighbors to meet police halfway.

“I'm not really sure what more you can ask your professional leaders in the community to do if residents aren't going to do their part,” he said.

The nonprofit encourages residents of the Southeast Community to do their own work to keep the neighborhood safe. It offers public safety and crime prevention training to residents and business owners.

Thomas said concerns about over-policing ignore the prevalence of local violence.

“How can we say that we, in the Third Ward, in poor communities, have a problem with (too many) police officers?” Thomas said. “Where do you think they’re supposed to go?”

A core service of the Grand Rapids Community Media Center