As Grand Rapids wades waist deep into the GR Forward planning effort this fall, the opportunities are intensifying for residents to contribute to plans that will define our community for decades. GR Forward is a comprehensive planning process of Downtown Grand Rapids Inc. (DGRI), the City of Grand Rapids, Grand Rapids Public Schools and their partners to engage the public in envisioning the many ways to make progress towards a holistic vision for Downtown and the Grand River.

Grand Rapids is certainly not alone in its efforts to revitalize and restore its waterfront. Many North American cities began their transformation decades- or even a century- ago, investing millions, and even billions, in their city’s future ability to manage the impacts of climate change, become a healthy place to call home and to promote a welcoming and inclusive place that matters to everyone.

So what can Grand Rapids learn from these pioneering communities, specifically in the area of creating new public lands that typify more sustainable development?

One project worth highlighting is the Muddy River Restoration Project, part of the Emerald Necklace park system in Boston. Although it isn’t the size and volume of the Grand River, it has many characteristics that can be applied in the area of flood control, water-quality improvement and habitat enhancement - all while honoring the history and landscapes of Frederick Law Olmsted’s and his belief in the social value of parks and natural areas.

Frederick Law Olmsted, his sons and as his partners Charles Eliot and Calvert Vaux were responsible for the design of some of today’s most well known parks including Central Park. It was the development of Boston’s Emerald Necklace park system that brought a new understanding of the function of multiple parks working as a larger hybridized system of civic, ecological and infrastructural uses.

It may have been Eliot’s understanding and development of regional planning with the Massachusetts Water Resource Council or Olmstead’s work as the leader of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, but the idea that parks needed to function at a scale and function larger than the City emerged at the end of the 19th century. The Emerald Necklace was not the first park system that Olmsted developed, but it was the one that combined not only circulation and vegetation into tissue, but a functional hydrologic system.

Much of the development of the system ran in parallel to the development of the city and necessitated a response as trash and sewage pressed up against the growing city, clogging tidal and fresh waterways. Even at the time, the Emerald Necklace was believed to be a large land grab. Had he only known the value of the land that was saved today and the subsequent real estate values adjacent to his landscapes.

Nearly a century later, it feels as though Grand Rapids is on the cusp of having the opportunity to make similar bold decisions that could benefit generations to come by implementing the restoration of our own Grand River, the interconnectedness of riverfront parks and the use of parks as infrastructure to function beyond just meeting the recreational needs of the community.

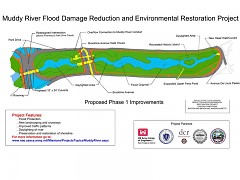

In 2012, and years in the making, the $93 million Muddy River Restoration Project began the restoration of the Muddy River that runs through the heart of Boston’s Emerald Necklace. The first phase of the project re-opened parts of the 3.5 mile stretch of river that had been covered or impeeded over the years, installed larger culverts to improve water flow and made other habitat and landscape improvements to the surrounding parklands. There are some key qualities of the project that are particularly appropos for our own community.

Flood Control Improvements: Decades of altering the flow of the Muddy River and new stormwater pressures resulted in major floods over a decade in the area, the last one causing over $60 million in damage. The restoration project improves flooding control by daylighting parts of the river, restoring river edges and riparian areas, removing invasive plant materials and dredging to restore the width and depth of the river to improve flow.

Water Quality Improvement: The Muddy River Restoration Project improves water quality in the river itself and also improves the quality of stormwater entering the river from local storm drainage systems. Much like Grand Rapids, the water quality is impacted by urban stormwater runoff, which carries sand, sediment and various pollutants from streets and parking areas into the river. Also similar to Grand Rapids, Boston has all but eliminated combined sewer overflow (CSO) but still experience occasional discharges of raw sewage during major storms. The project has called attention to constant monitoring and the need to work with other municipalities in the watershed to ensure everyone is committed to a clean river, all the time.

Habitat Enhancement and Landscape Improvements: The Muddy River Restoration Project will enhance the wildlife habitat in and adjacent to the river. Habitat refers to the nesting, breeding and feeding places for a wide variety of birds, mammals, invertebrates, fish, amphibians and reptiles that populate the river and adjacent parklands. True to Olmsted’s vision, the original landscapes were designed to create rich habitat, but invasive species have choked out many varieties of plants and wetland species. The project also includes the rehabilitation of elements of the historic landscape, within four sections of the Emerald Necklace.

The unsung hero of this project is the ongoing attention to best management practices and the presence of a citizen group called the Maintenance and Management Oversight Committee that ensures the project continues to receive attention and support for future phases. It is a complex project involving many partners, many agencies, many funding streams and many stakeholders with competing values. So having a group that continues to shepherd the project is essential.

As the GR Forward planning process enters into the next phase of gathering community input on the future of Downtown and the river, I hope you’ll join the process and be a voice for river restoration that includes creative approaches to riverside recreation, flood control, habitat restoration, historical and landscape improvement and water quality improvements, all while keeping our eye on the ongoing need for oversight and management of that future resource. We all need to channel our inner Olmsted and create a bold vision for our park system along the river's edge that inspires coming generations, while keeping our basements dry and our river clean. If we do it well, then the project will not only be restoritive for the river; it will be restoritive and personal for us all.

About the Author:

Steve Faber is the Executive Director of Friends of Grand Rapids Parks and is currently a member of the River Restoration Steering Committee, River Corridor Plan Steering Committee and Downtown Steering Committee. The views relected in this article are his own, and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of GR Forward partners, its consultants or members of these steering committees.

He would also like to personally invite you to the GR Forward Open House scheduled for Friday, October 17, 4-8 p.m. at 50 Louis St NW.

The Rapidian, a program of the 501(c)3 nonprofit Community Media Center, relies on the community’s support to help cover the cost of training reporters and publishing content.

We need your help.

If each of our readers and content creators who values this community platform help support its creation and maintenance, The Rapidian can continue to educate and facilitate a conversation around issues for years to come.

Please support The Rapidian and make a contribution today.